A Character in World Poetry Called Petőfi

Two hundred years ago a poet, considered by Hungarians to be the epitome of a poet, was born. When, as a child, I told my parents and grandparents that I wanted to be a poet, they laughed. My family had been poor farmers for centuries. There was not even a teacher among them. Farmers become farmers, not poets, my parents thought and laughed, but some children are crazy. He’ll outgrow this, the way children outgrow their clothes. But I was determined, so as a final argument they told me that there already is a poet: Petőfi.

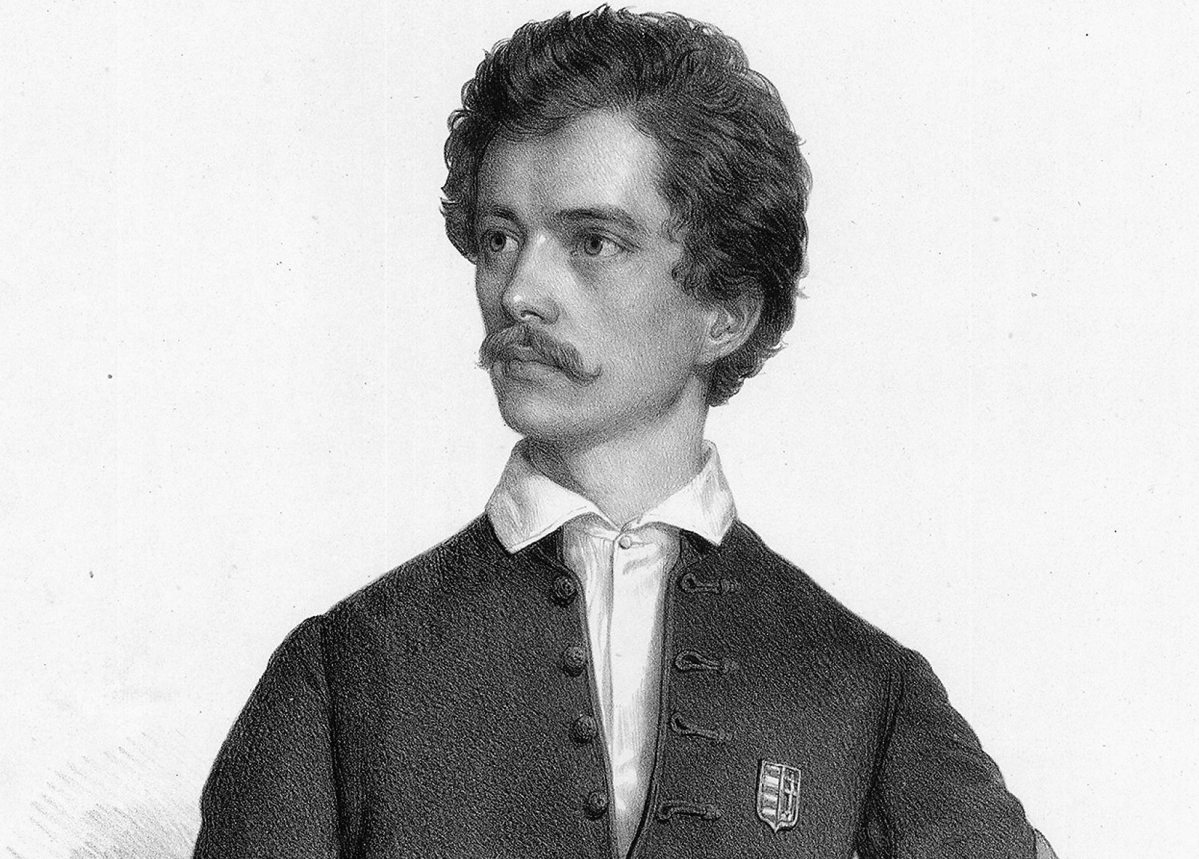

In Hungary, Petőfi is synonymous with the word poet and the profession of poet. He becomes part of a Hungarian baby’s basic vocabulary after words for mother, father, food and drink. We talk about him, we’re familiar with his poems, and we study and celebrate his life and work. Now more than ever, on the two hundredth anniversary of his birth, there are theater performances, concerts, and educational programs, which the state supports and the public enthusiastically participates in, because Petőfi belongs to every Hungarian.

But why write about him for foreign readers? Why should I, a living Hungarian poet, relatively unknown to foreign readers, write about a deceased colleague, also relatively unknown to foreign readers?

Petőfi and I represent a tiny linguistic community compared to the speakers of English.

These questions came to me when a foundation grant offered me the opportunity to present Petőfi to an audience in India. I realized that the only justification for the lecture would be to cast light on what is universally relevant to poetry and to modern literature, through the prism of a foundational figure of Hungarian poetry. To demonstrate that Petőfi’s personality and the poetic fabric of his oeuvre – presented in the context of literary creation in general – can be enlightening to anyone interested in literature.

Let us begin by examining the era we are talking about. When did this poet live, and what was happening on the world poetry scene at that time? Indeed, did such a scene even exist? In a letter, Petőfi complains that publishers reject poetry because they are interested only in profit, so they print novels by the thousands. This sounds like a current complaint, but we’re talking about the 1830s, when poetry was not as marketable as prose, even though anyone capable of writing wanted to be a poet, not a prose writer. Being a poet may not have been as advantageous financially, but at least poets were lionized at the time. This was the era when, wearing the mantle of Romanticism, modern poetry created the models of poetry and of what counts as poetic – models that are followed to this day, the world over. It was at this time that epoch-making figures came to the fore: Pushkin in Russia, Mickiewicz in Poland, Shelley, Keats, and Byron in England, and somewhat earlier, the Germans – Goethe, Schiller, and Hölderlin. They were scandal mongers, intensely obsessed authors, oftentimes freedom-fighters, some of whom gave their lives in their struggles. Shelley and Byron fled England because of scandalous love affairs, Pushkin died defending his honor in a duel, and, like Byron, my hero Petőfi perished on the battlefield in defense of liberty. The events surrounding their lives show that they were the rock stars and celebrities of their age, which the contemporary press constantly and loudly reinforced. Consider this one example from the mid-1810s: Shelley, Byron, Mary Shelley, and Byron’s former pregnant lover cast aside all social norms, fled from family and wife, and camped at Lake Geneva, where Mary created one of the great horror-story heroes, Doctor Frankenstein. So many outlandish adventures are attributed to this group, a druggie tripping on LSD couldn’t invent them all.

But they – unlike the inane celebrities of today – amid all their swagger, laid the foundations of modern poetry and – not least – of modern literary language. It is their language we speak, their language we can read without a dictionary, because that is our mother tongue, not just in a linguistic sense, but on an emotional level as well. After all, they put in words the fundamental problems of modern man. They wrote the first significant works of psychological insight.

A few years ago in Warsaw, I was in the company of a group of intellectuals, including university professors, mostly women. At one point I noticed that they were talking about a man called Adam. Everyone had something to say about him. Adam was so handsome, Adam was a fantastic writer, Adam was such an impulsive man and thinker, and what a brilliant mind! I started feeling uneasy. After all, there I was in the flesh, and yet they were gushing about someone else. Finally, I asked the teacher sitting next to me who this Adam is, and she casually said Adam Mickiewicz. Even though he was being referred to as if he were right there, among us, I knew that he had been dead for a hundred-fifty years, and so I was relieved that Adam was not a rival for these women’s attention.

As this story shows, to this day these artists are fundamental national figures, and as such they were quite similar to one another. They played very similar roles in the history of their nations. They championed freedom, love, independence, and personal autonomy. They were the first who dared to embrace a life free of social constraints, based on equal opportunity and respect for human dignity. They laid the foundations of all revolutionary ideas. Every free lifestyle can be traced back to them, or almost all, since they would not have supported consumerism.

One of these great artists is Petőfi, who created world-class poetry in a language not widely known, and spoken by very few, but who was included in Victor Hugo’s famous poem “Carte d’Europe”.

He is the man who was translated into countless languages during his lifetime, and continues to be translated to this day. It is thanks to him that the freedom-loving Hungarians became fashionable, as did – to some extent – their language. He was the favorite poet of Nietzsche, who set six of his poems to music, after all, the philosopher who articulated modern disillusionment wanted precisely what Petőfi wanted: to radically transform the world, to do away with mediocrity in favor of genius and the affirmation of life.

Every new generation, whether in civil life or in the arts, wants to assert itself. Its aim is to take over the power, the control, and the decision-making of the older generation. And however much the old generation clings to its power, change is inevitable. Previously maybe deftness won the day, in the modern age knowledge wins. The world’s technological transformation is happening so rapidly, that above a certain age a person can’t even comprehend what’s going on. By the time we master some device, it’s unavailable. In the field of art, on the other hand, the new is about the valid expression of newness. Canonized literary language becomes obsolete, loses its impact and connection to reality. It becomes classicized and boring. I remember, when I was young, being amazed to find out that some older writers were still alive; they struck me as being dead, because artistically they were dead. That’s when young people come along and say, we need a more expressive language, something that speaks more authentically about the world. Truly, they don’t want to dethrone these eminent writers. They don’t want to wipe out those who came before them. They just want an authentic language, one that can be used to challenge the dominant language, to challenge the right of those dominant-language users to rule the day. To take an international example, Flaubert’s realist language challenges Dumas’s language and the kind of romantic narrative he represented. Compared to Flaubert, Dumas is ridiculous. The poetry of the early 19th century stands in contrast to classicizing language, packed full of mythological allusions and cultural platitudes. There’s no need for such loftiness.

In general, this kind of language-change is like a revolution, moving a language from the periphery to the center of society. In European literature, this change was accomplished by folk poetry. Petőfi’s linguistic innovation was his rejection of the customary Greek-like Classicism, and his creation of a poetry based on simple meter and rhymes, a poetry closer to everyday speech than to Greek or Latin classics. This mode of expression was a revolutionary innovation that produced countless masterpieces. It also established Petőfi in one of his most important roles: he became the poet of the folk song. This is not an easy role, since the basis of folk poetry is natural speech. A folk-song writer creates a song once or twice in his life – for example, when he is in love – and he is able to convey this feeling with genuine naturalness. Simple images, simple messages, clear emotions. Here is a classic Hungarian folk song, “Tavaszi szél vizet áraszt” (“The Spring Wind Makes the Water Rise”):

The spring wind makes the water rise.

Oh my love, my flower,

And every bird selects a mate,

Oh my love, my flower.

I now must choose a mate, but who?

Oh my love, my flower.

Will you choose me, as I choose you?

Oh my love, my flower.

The role of the folk poet was so important to Petőfi that he actually walked about in Budapest dressed in peasant garb, just to appear more authentic. “I am the folk-song poet, the son of the folk,” his garb proclaimed. And this poetry proved successful, because a few years later, when the Hungarian Society of Scholars organized a drive to collect folk songs, dozens of Petőfi poems found their way into the resulting corpus. These Petőfi poems were sung to the melodies of existing folk songs, and people could not tell the difference.

Before going on with listing the types of poetic roles, we should ask a basic question: What is a role? When a writer begins writing, he must first and foremost be aware of this: What he feels is not what matters; rather, the feelings expressed in the text are what matter. This means nothing other than maintaining a distance between the emotions and the subject of the work. This seems like a contradiction in art theory, because that distance must be maintained while also maintaining a connection with the artist’s heart, which nourishes the work. The poet’s role takes shape when this distance is created. This is when that “someone”, whose voice speaks in the poem, takes shape. In other words, the separation of the self who speaks in the poem, and the private self.

Of course, we all play roles: to my children I’m their father, in a shop I’m a customer, to my mother I’m her son, we are teachers or doctors. Everything is a role, because we cannot speak the same way everywhere. The role is the basic tool of the artist. The writer must know who is speaking in the text, and from where. We need to be familiar with his personality, and we need to know what he knows, what he is familiar with, what he sees of the world. If the role is very alien to us and to the writer, it will easily become mannered or affected. If the role is contrived, we don’t believe it. Furthermore, if the role is too close to the writer, the danger is that his own personality, his private feelings, will take over, and the reader will not be able to recognize himself in the text. And we always want to read about ourselves in every literary work.

If one’s role is a matter of choice, and not a requirement imposed by circumstances, it must be chosen with ingenuity. And flexibility – knowing what is appropriate – is also required. We don’t want to sound like the parents of our colleagues at work. A common management error is when the boss behaves like his staff’s friend, and doesn’t understand why they are afraid of him even so. If it’s clear who is speaking in the role of boss, things become easier and more natural.

When poets seek inspiration, and look within themselves for emotions that can bring forth a poem, they are usually in quest of a role, for example, the role of the jilted lover, of someone in anguish over the fate of mankind or over his personal torment. Once they find it, the poem is almost finished. This is because the role will shape the way of speaking, the subject, the thoughts, even the versification. A revolutionary does not speak like a lover. Of course, it doesn’t hurt to have some talent, because without it, we’ll just be bad actors and not creators.

Petőfi seems to have known all this instinctively, and was a confident role-chooser from the start. First of all, Petőfi was not Hungarian. His parents were Slovak. His first role was to be Hungarian, master of a language he learned, hero of an assumed identity. These lines from his famous poem, “Füstbement terv” “Plan Gone Up in Smoke”: “All along my journey homeward / I pondered fitting words to say / When laying eyes upon my mother / From whom I’d been so long away”, refer not to whether he would say “my dear mother” or “my sweet dear mother”, but to whether he would address her in Slovak or in Hungarian.

As with all extraordinary persons, his birth is shrouded in legend. It is not known exactly when he was born, on 31 December 1822 or on 1 January 1823. Two Hungarian towns are vying for the honor of being his birthplace. Of course the point is that he was born, moreover into a Slovak family. His father was an aspiring entrepreneur, a pub owner and butcher. It is important to know that, at this time, there was no independent Hungary. Hungary was part of the Habsburg Empire. Decisions concerning the country were made in Vienna, at the imperial court. It is important to know that this was a multi-ethnic empire, in which the various nations and nationalities were already formulating their aspirations for independence at this time. Petőfi’s Slovak family lived among the Hungarian majority, and intended to integrate into it.

But let us return to biography. You can say the little boy was quite well-off. The father had the means to send his son to the best schools, no matter the cost, because he was convinced this boy was going to become somebody. At nine, the boy left home and went to a boarding school, then to another. The father always wanted what was best, so if the child wasn’t doing well somewhere, he immediately enrolled him somewhere else. This went on until Petőfi, at the age of 15 or 16, tried to leave school and become an actor.

Acting at the time was like rock music in the sixties. You didn’t have to know much about music to join a band and you were definitely considered very cool. Petőfi’s first attempt was thwarted by his father, who gave him a sound thrashing. But a year later, he was already a member of a traveling company. In those days there weren’t any theater buildings. These acting companies wandered from town to town and performed in pubs, living off donations from the public.

This was how Petőfi learned what it means to assume the guise of others. He worshipped acting, though he had no talent as an actor. It was said his voice was grating, and his laughter revealed an unsightly row of teeth. Soon he left the profession and made a new attempt at a life: he joined the army. He was not yet 18, but lied about his age. He thought he was going to see the world, but all he did was fall ill and get discharged. What could a failed actor and failed soldier do? He had no choice but to go back to school. That choice couldn’t pan out, however, because by then his father had failed as a businessman. Thus Petőfi went from being well-off to poor, and had to scrape together the money for school himself. This was the basic grievance of Petőfi’s life. He experienced poverty. Although he did not hail from the ranks of the simple folk, his own experience helped him to identify deeply with the vulnerable, with those relegated to the dismal reaches of the world.

Here we must pause for a moment. We are back at a fundamental question relating to the psychology of art. Every artist suffers some kind of grievance. This grievance is what drives him to create. A grievance elicits the feeling that things are not right with the world, and that I as an author must set things right. Every new work is an attempt at setting the world aright. But since the world cannot be set aright, there is no end to the undertaking. All authors work from their grievances. The impetus behind their work is the emotional energy that springs from their grievances. In the case of Petőfi, it is through the financial decline of his family that he confronts a world that is not right. He wants to redress his personal grievance, but he experiences that as a general grievance. He identifies with the fallen, with society’s losers. As a consequence, improving the lot of the community becomes the most important thing for him.

But let’s get back to his biography: Petőfi at this time was not Petőfi. He had a Slovak name, Petrovics, but he decided to become a Hungarian poet, and kept writing more and more poems. And all of a sudden, surprise-surprise, a then-famous journal accepted and published his first writings. One of them was Bordal (Wine Song), in which he praises the beneficial effects of wine.

He wrote many poems like this, in which the intoxicated protagonist seduces and ravishes women. Here he assumes the role of a fashionable artist, the bohemian author. Because of this role, my father, for example, thought that he would never let me become a writer, because writers are alcoholics or drug addicts, and slackers. It should be said, however, that alcoholic writers, like Faulkner, were not able to write while intoxicated, because that can’t be done. And here we come to another important point: writing involves the deepest possible concentration. If we can’t pay intense attention to what we’re writing, we’re sure to fail. The oeuvres of addicted writers like Baudelaire, Malcolm Lowry, or Céline – albeit highly influential – are modest in size.

Or, more generally, how does the self that emerges in the poem relate to real life? How does the role relate to reality? Of course, no one can answer this precisely, because there is no objective way to measure the extent of personal reality in the self of the work. Some writers put more of their own self into the text, others less. The Romantic poets played with the written self as identical with myself. The modern poets, Eliot, Ezra Pound, were more concerned with removing the personal self. One thing is certain: the person who emerges in the text and the person who lives in reality are never the same. Not even in autobiographies. Consider someone relating his past. If he’s married, the story is completely different from two years later, after divorce. The narrative of our past is always shaped by our current situation. For example, I was a pretty good math student, but my math results are irrelevant in light of what I became. When we talk about ourselves, about our lives, we highlight certain things, and leave other things sketchy. Hence all narrative is fiction. Every character, even our own representation, is a role.

Petőfi’s wine songs and merrymaking poems are the best examples of this, since the well-known fact is that our poet never drank, and in the company of women he became as tense and inhibited as any shy boy. But that’s not important. What’s interesting is that the people loved those poems; in that age, poems like this were all the rage, and Petőfi was talented enough to imagine this wine guzzling, intoxicated persona, to find within himself the freedom of intoxication. In any case, he was so widely known as a drunkard that when he visited a writer friend, Mór Jókai, his host’s mother filled the guest room with bottles of wine, lest the poet’s thirst should keep a poem from being born. And when Petőfi told her that he didn’t drink, she assumed he had just quit.

So what was the character of this young author, who at this time was still hardly past adolescence, but whose name was already known nationwide? Everything was said about him, and so was its opposite: He was an irritable know-it-all, and at the same time a devoted, helpful friend; he craved being the center of attention, but often stayed quiet at the sidelines. Some people hated him, not a few, sooner or later he fell out with all his friends. He spared no one his opinion; he was maniacal in his quest for the truth. He was feared and dreaded by those less talented than he was, and everyone was less talented than he was. He was like most self-absorbed adolescents, thinking he was going to change the world. The difference in his case was that he actually did something to change this world.

He was a writer of folk songs and wine-drinking songs, but that role was not enough for him.

Where is the self that sings of love? He’ll do anything to find inspiration. Here again we must stop for a moment. The greatest problem in the life of an author is when he cannot speak, when he cannot write. Because artistic creation is not like the work of a craftsman, for whom the more he does it, the better he gets at it, and the easier it becomes. A craftsman’s knowledge is not enough for artistic creation. You need inspiration. One way or another, everyone wants to be potent; everyone is searching for intellectual Viagra. Everyone invents things, but inspiration either comes or it doesn’t. This was a problem for Petőfi too. He tried everything. The catalyst that most spurred him on, to the end of his life, was resentment at not being appreciated enough, even though he was the greatest. The other catalyst was love. At the beginning of his creative life, he made an attempt at love. One of these legendary stories is when he tried to kindle love within himself toward a friend’s deceased daughter. She had died young. Petőfi got so involved in this role that he moved into the deceased girl’s room. For the artist, nothing has too high a cost. He will do anything to bring a poem into the world. Because a writer’s talent depends on writing. When a writer doesn’t write, no one is less talented, because he remembers what it was like when he wrote.

This was when Petőfi’s corpus of love poetry began growing. I remember an amusing interview in which a poet was asked why her work is special. Without batting an eye, she said it was because her subject-matter is special. The reporter then asked what that is. Her reply: I write about love and death.

With Petőfi, it is particularly interesting to see the emotions of someone who is barely an adult. And thus, all his enthusiasm for love involves only two characters: himself and love itself, the object of that love is no more than a set piece. Perhaps little was known at that time about this psychological process, but I suspect that Petőfi was simply too young, he was excited less by the object of his emotion than by the emotion itself. That is why he fell in love with anyone, if that anyone could inspire poems. It’s a true wonder that a few years after this initial fervor, some brilliant poems were born which plumb the depths of emotion by simple means, such as “I shall be a tree, if you are its blossom, / Or I’ll be a flower, if you are the dew”, or “A flower can’t be told / Not to bloom in springtime”. Or perhaps “Minek nevezzelek?”, “What Shall I Call You”, a poem about a real love, written for his wife. Because our poet had a wife. One of the targets of his love poems took him seriously and signed on for life with him, though the poem that convinced her was intended as a farewell. Right at this time Petőfi was about to marry an actress, but he couldn’t help it – he ran back to his previous selection. This is the moment when the role gets intermixed with reality. He was twenty-five when he married. I was also twenty-five, but that doesn’t mean that poets, or specifically Hungarian poets, get married at twenty-five. Some don’t get married at all.

Whatever the catalyst, whether the intrinsic drive behind Petőfi’s poetic expression was love or even resentment, it worked brilliantly. Seven creative years produced a complete oeuvre. There was a year, 1844, when he wrote more poems and epics – epic poetry being in vogue then – than other poets wrote in a lifetime. This was the year his ever-popular folk-epic, John the Valiant, was created. Legend has it that he wrote this book-length poem in six days and six nights, the same amount of time the Biblical God took to create the universe. This seemingly unbelievable claim is probably true, because he couldn’t have had much more time for it. John the Valiant is a playful poem. It is about a shepherd boy driven from his village because instead of tending the sheep, he has been dallying with his lover. Our hero then enlists as a soldier and his heroic exploits involve rescuing the French Emperor’s daughter from the Turks and saving France itself. In vain is he offered the hand of the French Princess, he longs only for his Iluska back home, and finally, after newer adventures in the realm of the fairies, he finds her. This adventure story is replete with emotions, heroic deeds, and astonishing, often amusing episodes. Every little boy wants to be like Valiant John and every little girl wants to be loved the way Johnny loves Iluska. This work generated a multitude of ballad operas, animated films, puppet shows, and stage plays. If it had been written in English instead of Hungarian, Hollywood or Bollywood producers would have snapped it up long ago and it would be a world sensation today.

Petőfi wrote as if he knew that he must not pause the creative process, because for him, time was short. One wonders if there may be some secret sense that tells us we have only seven years to create an oeuvre, a lifetime of work. Van Gogh too – it’s as if he knew he had to create a life’s work in four or five years, because no more time would be available to him. Or is it only posterity that considers even a truncated oeuvre as complete?

One thing is for sure: we never think of Petőfi, Van Gogh, Caravaggio, Rimbaud, Pushkin, and Byron as artists who did not finish their life’s work.On the contrary, we regard them as having left behind a complete oeuvre.

Petőfi’s seven short years fell at a time when the idea of independence was gaining momentum in Hungary. A wide variety of groups wanted to free the country from Habsburg oppression, feudal laws, and backwardness. The most radical of these groups and movements were the students. Even among them, Petőfi was the most vocal and radical. His poetry-nourished ego now saw himself as a leader of the people. He spoke up in the name of the people with increasing frequency. His banner was blazoned with the ideals of the French Revolution: liberty, equality, fraternity. His poetry increasingly pertained to public life, and by 1848, the year revolution broke out in Paris, Vienna, and then Pest, he was the spokesman of the people. The ideals of the French Revolution were now sweeping the country. A poem Petőfi created then, the National Song, was publicly read innumerable times on March 15, the day the revolution broke out. Petőfi, employing all his acting skills, recited it himself. To this day, we regard this poem as the anthem of Hungarian liberty, and whenever Hungarians feel their freedom is in short supply, they turn to it again and again.

We have now come to another role, the final one, which – so to speak – takes the helm in Petőfi’s poetry. It is not a role alien to poetry. After all, the greats of the age were all drawn to revolutions that sought to erase the past; they were drawn to changes that could bring about a society in which everyone is of equal standing, and neither wealth nor social rank determines one’s place in the world. Even today, this is what every thinking person, every artist, wants. For an artistic creator, it is difficult not to take the side of the destitute and underprivileged. Because to create is – in a way – to empathize with the plight of others, to feel their misery, and when you do, you cannot but act to change it. Petőfi in particular knew about rank and wealth. There was a time when his family was well-off, then he experienced impoverishment and destitution. Moreover, he never had rank, because his family didn’t belong to the nobility, on top of which, he was Slovak. So even as a well-off child, he lived a second-class life.

The revolution achieved its goals. The imperial court backed down. Unfortunately only for a time, because eventually it attacked the new Hungary. At the beginning, the Hungarian armies fought skillfully and routed the enemy, but eventually the Austrians, with the help of the Russian Tsarist armies, defeated the revolution.

But let’s step back a bit in time: We are in the final months of the revolution. Petőfi by now is not a simple leader of the people, but a producer of political poems agitating for holy war, calling for the dethroning of kings, and sounding a call to arms, whatever the cost. In one of his poems, he writes that he does not want to die in a bed among pillows, but on the battlefield. The messages of these poems are clear and simple. Now, for the second time in his life, something happens which a poet must not, in principle, allow: the distinction between the one whose voice we hear in the poem and the poet’s private self vanishes.

The first step an amateur writer must take to become a real writer is to create the requisite distance between his private self and the self that speaks in his work. When this distance is lost, the work and the author become conflated. This is what happened in the final months of Petőfi’s life. “If you want to fight so much,” everyone around him said, “why aren’t you on the battlefield?” Even his wife told him that he calls his own poems into question as long as he doesn’t enlist. But Petőfi was not a soldier. He was a sickly, fragile poet, unfamiliar with the ways of soldiering, and he had no skill with weapons. In addition, by then the war of independence was in ultimate danger. The Hungarians were so overpowered that defeat could be the only outcome for them. And so it happened that in one of the last battles, when the Russian army was crushing the Hungarians, some witnesses said the poet was impaled by a Russian soldier.

His body was never found.

Therefore, no one wanted to believe that he was not alive. He was thought to be wandering in disguise for fear of reprisals. In those days, if someone knocked on a door in Hungary and said he was Petőfi on the run, he was sure to be given a meal and a bed for the night. That’s how beloved this poet was. People believed he was alive, the way Elvis Presley fans believe that Elvis lives on an island and sings “Love Me Tender” to the birds three times a day.

There were those who believed Petőfi was dragged off to Russia, where he began writing poetry in Russian. His body was repeatedly searched for in remote areas of Russia. Not so long ago, a Hungarian businessman financed an expedition to Siberia to repatriate the bones of the supposed Petőfi. The remains were allegedly smuggled across the border in a suitcase. Scientific examination eventually identified a female skeleton which was not the LGBTQ version of Petőfi.

Everyone wanted him to be alive. Well, not the authorities, only the people. It would have been good to see him rebelling against the prevailing powers, against injustice, but he is no more, only his legend and his poems remain as pillars of any movement dedicated to building a better world. To be a support to all well-meaning people the world over.

Translated by Eugene Brogyányi

It was originally published in The Continental Literary Magazine.