I never wanted to be an Indian

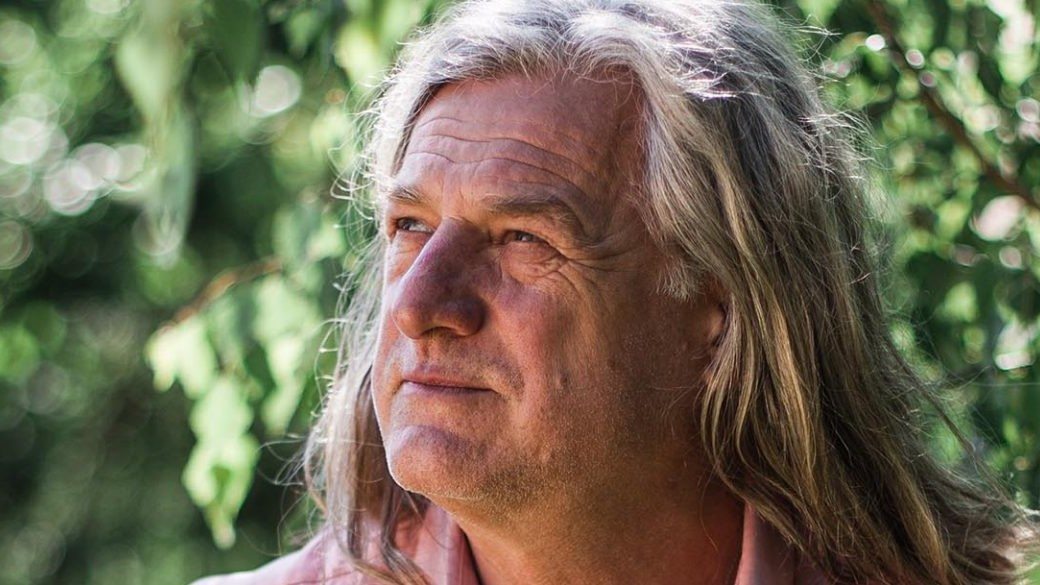

Hungarian poet and translator Gábor Gyukics talks about leaving Hungary in the 80s as a political refugee, his time living, writing and publishing in the US, and his years of translating Native American poetry.

How did you end up being the number one translator of Native American poetry?

When I went back to St. Louis to visit my friend, Michael Castro, and some other great poets, I met an Osage Indian, a Native American, named Carter Revard, who is probably eighty-something now. He was the professor of English literature, I think he graduated from Oxford, summa cum laude or whatever you call it, and from Yale – two of the world’s great universities. He had never met a Hungarian and I had never met a Native American. We started talking and I invited him to give a lecture, a poetry reading at Petőfi Literary Museum in Budapest.

I think it was 2005 and there was a great crowd. He came back a few years later and did another good reading, his poetry wasn’t the first that I translated but the last time he left Hungary he told me “Gábor, I’m not the only Native American poet” so I said, ” don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to be sarcastic, please send the smoke signals to the other Native Americans that there’s a crazy Hungarian who wants to read their poetry and translate them into Hungarian. If they don’t mind being translated into a language which is only spoken by 15 million people.”

So I got a lot of poetry, at least 50-60 people and then there was no stopping it, I had to go on and I’m still translating for Native Americans. I visited the Flandreau Reservation as well, where Jim Northrup lived. I published his book, and I published a Native American poetry anthology five years ago as well. So two Native American books. And I translated one of my favorites, Lance Henson – he’s an exile because he’s a revolutionary, and they don’t like it when he goes back to the States because there is always turmoil when he goes back. I think he used to work for the United Nations dealing with indigenous issues, so he went to Papua New Guinea and other places around there. He visited the Natives and tried to voice their struG.Gy.les to UN authorities. He is a great poet and writes very short poetry like my mine. He is kind of a minimalist but it’s very strong stuff, and it turns out that he was a Dog Soldier, who are known to be fearless Native American warriors.

How did you get in touch with the Dog Soldiers?

The way I got in touch with the Dog Soldiers was to just call Lance and see what he says. I mean he tells me that this is a very old society of the Cheyenne tribe. When the first white people arrived, the Cheyenne gathered together and decided they have to fight these people, so they assembled many people and created a warrior society called the Dog Soldiers, and Lance, as well as his son, are members of this society. And one of the rules – and I think still is, but it might not apply for new members – was that

– you can’t just rob a house and kill the lady there and the nurse, you have to kill someone in combat to be accepted.

As a translator of Native American Poetry, how do you see the situation of the Native Americans in these difficult times…

Well, in general, I see that the Native American situation in America is very tough and possibly harder than the black people’s situation there. Minorities are not treated well by either the Republicans or the Democrats or anyone else for that matter. Racism is on the rise, right-wing groups are on the rise. Armed right-wingers! And they hate people of color. Period. Native Americans are prime targets of these right-wing groups. More Native American women disappear every year than from any other minority group. They are raped and killed by white policemen, white sheriffs, white hunters, and farmers, who don’t get punished. That’s a scandal, and nobody does anything about it. The Native Americans raise their voices sometimes, but they get no answers or responses. So they have to deal with this. They can’t figure it out, I don’t know how they want to protect their children but it’s very hard for them because so many tribes are living in poverty. Some groups got lucky because of the casinos and in other ways, but many, I think there is an Apache section, you go into their reservation, and it’s like the ghetto. It’s terrible – no running water.

How many Native American poets did you translate?

Native American poetry and art are very strong, and I translated at least 50 but probably more, Native American poets. I do it daily so I always pick up new people and because several young poets are emerging now, so probably 50 to 60.

When you are visiting the States and visiting Native American poets, how do they treat you? How do they welcome you?

If you are an American white person, they don’t like you. If you are European, there’s a chance they will like you a bit more. But they give you a test. At first, you don’t even realize it’s a test. They start pushing you. They say nasty things. And if you get offended, they don’t care for you anymore. If you take it and answer with humor they laugh and say “OK! He is a nice guy!”

You can read more stories about the exciting life of Gábor Gyukics, William Burroughs and Indian casinos in The Continental Literary Magazine.