From clay to lace and beyond

Dedicated Hungarian artisans keep centuries-old traditions alive, crafting a cultural legacy that blends history, community, and artistic excellence.

Slipper making

Slippers became a part of women’s week day and holiday wear and men's week day wear in the 19th century. Taking over civilian wear and the streets cobbled after the great flood in 1879 both facilitated the spread of the slippers. The way they are made and decorated provide their uniqueness and their special Szeged quality.The traditional Szeged slippers were ‘one of a kind’, because only one last was used for making both the right and the left sipper. The right and left versions were shaped while they were worn.

As slippers were made by bootmakers, not shoemakers, fitting the parts of the slipper was made as it boot making (inside out while wet). The upper part of festive slippers for women could be made of leather, velvet, silk or fabric decorated with flitters and beads. The Szeged slippers are still part of the new wife's clothing at Szeged weddings and they are also used by folk dance groups nationwide. Their modernised versions are more and more popular in everyday life.

Pottery

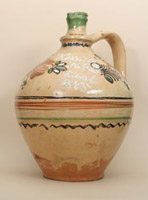

Mezőtúr

In the mid-19th century pottery making rose to fame among the abundance of rich handcraft traditions in Mezőtúr – a town in the southern part of the Great Cumanian region of eastern Hungary. The practical household crockery as well as the exclusively decorative pieces quickly spread throughout the country.

Historically Mezőtúr earned a place of distinction for its country market-fairs and its crockery – a heritage that is still very much alive and continually developing today. The bearers of the knowledge amassed over the years are those local workshops and small-scale ventures where locally trained masters practice and also teach their craft to future generations.

These workshops not only produce articles meeting modern tastes and uses, but are the scenes of significant preservation work as well. The elements of a well-developed, rich culture refined over hundreds of years are preserved in the fired pottery and in the technical knowledge and expertise of masters. The pottery-making tradition in Mezőtúr is not merely a way for local masters to make a living. It is and has been a point of pride for the entire town, providing and reinforcing in Mezőtúr inhabitants a sense of identity over the ages.

The local tourism is also largely based on this culture. Fortunately, Mezőtúr and its citizens recognized the value of this heritage and the need to take steps for its safeguarding in time. Without any outside intervention they managed to establish quality task-oriented institutions (museums, rural heritage houses, art schools, etc.) suited to preserving this cultural heritage and transmitting it to future generations.

Magyarszombatfa

Magyarszombatfa is located in the west side of Hungary, in Vas County, at the southern boundary of the historical Őrség, alongside of the Hungarian-Slovenian border. The pottery tradition of Magyarszombatfa primarily includes the potter families in the village, who’ve continued the nearly 700 year’s old tradition in their workshops.

The clay with really good quality mined here fundamentally determines the pottery of Őrség. It’s an integral part of the heat-resistant pot dishes and has provided the traditional basis for the local potters for centuries. The most characteristic sign of the pottery of Magyarszombatfa is the North Italian faience type left potter’s wheel. The master sits to the right from the axis, so the disk does not take place between his legs.

In addition the pottery of Magyarszombatfa is characterized by an archaic pattern, from which some of them can be found somewhere else with different tracing, but there are dishes only typical for this region. The austere vessel forms with early modern origin are the main characteristics of them. In the first decades of the 20th century it was common almost in every household in that region to make clay pots. Later, only the bests continued the pottery tradition. During the 1920’s and the 1930’s more than one hundred potters worked in the villages of Velemér-Valley (Magyarszombatfa, Gödörháza and Velemér).

The symbol of the settlement’s pottery is a harrow walled, thatched potter house which has been built in 1792 and which is now functioning as a country-house museum in the care of the local authority. In this house the historical pottery of the Őrség region and its presence in the peasant household is presented by the village community.

Lace making

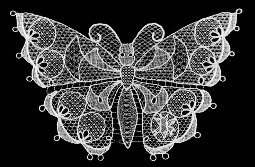

Halas

The town of Kiskunhalas in south-central Hungary is home to the more than 100-year-old world-renowned tradition of Halas lace-making. Árpád Dékáni a young teacher and Mária Markovics a plain seamstress were the creators of the unique sewn lace-making technique in 1902.

The making of Halas lace is a painstakingly tedious, time-consuming process that is done exclusively by hand with exceptionally fine white thread, practically invisibly thin needles and meticulous dexterity and attention to detail. Only select initiated lace-makers were privy to the coveted technique, whose numbers varied over the years between 80-100 women and has since dwindled to a mere 11. The official trademark of this particular lace – found even on the smallest 2-3 cm lace articles - is the symbol of 3 fish superimposed upon each other.

Even today the original century-old distinctive patterns and motifs can still be seen on Halas lace and the original unique stitching techniques are unchanged. Halas lace remains a symbol of not only the inhabitants of Kiskunhalas, but a unique example of Hungarian handicrafts.

Hövej

The ‘pókos’ (literally means spider) needle-lace origins from the village of Hövej. This still-living form of decoration has been appeared in the 1880s. The flower patterns middle holes are meshed with thin thread and then filled translucent web-like.

The most valuable piece of work is filled with a lot of web-like thread (‘pókozás’) and the interior filling of each flower motif is made with another ‘spider’ technique. The lace of Hövej is white coloured. Patterns, elements of stitches and web-like ‘spider’ spottings have been inherited through generations. The holes of the flowers are filled out with sewing needles this is the reason why this lace is also called lacemaking. Learning sewing begins in childhood and as soon as people get enough practise can try the most difficult task, the ‘pókozás’.

Love, endurance and last but not least patience are needed in order to learn the creation process of the Hövej’s lace. The residents are proud of the art of lace-making which both technically and both in richness of motifs has developed over the years. The heritage of Hövej's is a highlight of Hungarian folk art and can also be found in the village's coat-of-arms.

Bulrush weaving

The word bulrush represents both the plant itself and the carpet which is made from it. Both were parts of Tápé’s inhabitants’ life for centuries. The material was collected by the men and the warp yarn was drifted by children, young and old people from the ’selyöm’, which was pulled off from the edges of the plants’ leaves. The weaving was carried out mainly by women. Onto two-two pickets a rod, called ‘átalfa’, was placed and then the ‘ijan’ was perched to this after it was threaded through a rib.

Thenceforward the well prepared leaves were threaded through between them once from the right and once from the left. After pulling some thread, they compacted their weaving with a rib. The technique which was preserved for centuries has been passed on by many generations. This ongoing process was stopped at the second half of the 20th century, but there are still women nowadays who keep this tradition alive. Thanks to their work, the bulrush weaving is still an important part of the local people’s life.

Blue-dyeing

The spread of the craft of blue dye in Europe relates to the Flemish, who were maintaining this craft from the 8th century.The earliest craftmanship of blue dye was formed in Vienna in 1208. The first working partnership began in Hungary with the cooperation of the cities: Lőcse, Eperjes, Igló and Késmárk. In the second half of the 18th century were too many employees in the textiles and craft of tinctorial came into existence in the territory near to the Western part of Hungary.

Individual wanders and families settle down raising the numbers of those involved in the craft of tinctorials in Hungary. This is how the ancestors of Kluge family from Sorau, Saxony, continued the craft which took place over seven generations. In the middle of the 18th century the textile printing instruments used pigment and pickle squeezing, allowing the painters used the woad to produce the colour blue. However the carbon was already known in the middle ages, spreaded only after the beginning of the ongoing importing. One specialized branch of the blue dye craft, came about from the end of the 18th century, means the special process of the stanchion printing and textilepainting with carbon. From the 20th century beside painting with carbon appeared the synthetic carbon with better quality, the so-called „indantren”, and connection to that the stanchion printing spreaded. Both technology are presented in the limited workshops of blue dye craft in Hungary.

In accordance with the aims of UNESCO, the States Parties shall identify intangible cultural heritage elements within their territories and draw up inventories. In fulfilling this obligation in May, 2009 the Minister of Education and Culture has called on bearer communities, groups and individuals in Hungary to nominate recognized elements of their own Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) for inscription. Following the reccommendation of the ICH Committee, the Minister of Culture created two lists in service of the safeguarding Hungary's intangible cultural heritage, the National Inventory of ICH and the National Register of Best Safeguarding Practices.

For more Hungarian intangible cultural heritage, please visit this website.